Hello 👋

This week I have another personal essay for you. It’s about imagination, disappointment, and the games I used to play as a child. We’ve got Japanese woodcuts, untranslatable German words and even a quote from a physicist. Enjoy 😊

In my poll a few weeks ago several of you expressed interest in a half-hour consultation with me to talk through a design or creative challenge.

Whether you want portfolio feedback, creative support or just a chat, let’s talk!

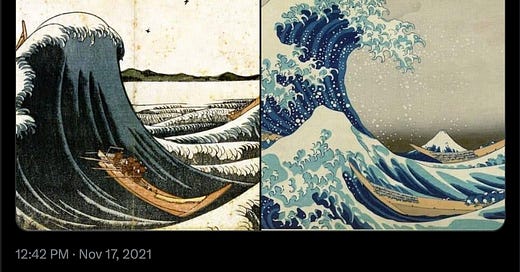

I’ve been thinking about this tweet a lot just lately1. It shows two versions of Katsushika Hokusai’s celebrated wave woodcut, made twenty-six years apart. I hadn’t realised that the Japanese woodcut artist made many variations of this famous image, variations that steadily increased in richness and complexity across his career. The final 1831 version on the right, with which we are probably all familiar, was made when he was seventy-two years old.

It is striking how much Hokusai’s technical skill has increased across the two images. The forms are more intricate, the colour is richer, the composition immensely more powerful. But what I think is most interesting to think about, and what Visakan’s tweet alludes to, is the way Hokusai nurtured this vision of a more splendid wave inside him for so long, for woodcut after woodcut, each one getting slightly closer to the ideal that only he could see.

The artist believed that if he lived long enough, this process would culminate in artworks that would be as alive as the phenomena they depicted. Imagination and reality entirely indistinguishable from one another. In his own words:

“Thus if I keep up my efforts, I will have even a better understanding when I was 80 and by 90 will have penetrated to the heart of things. At 100, I may reach a level of divine understanding, and if I live decades beyond that, everything I paint — dot and line — will be alive.”

—Katsushika Hokusai

Sadly, we live in a society that tends to treat imaginative powers with more than a small dose of suspicion. Whilst make-believe and fantasy are tolerated in the very young, at a certain age it is expected that childish things like this are put away. The real world is the domain of hard facts, numbers and common sense. The ‘dreamer’ in our stereotypes is naive, hopeless or a time-waster.

And as designers, we frequently have to reckon with the consequences of this. Finding ourselves in teams who regard time spent exploring framings of a problem or alternative possible solutions as an inadmissible luxury, or who dismiss the abductive leaps that designers make as lacking in rigour.

Even the very presentation of design as “problem-solving” that I used above, with it’s sheen of scientific precision, is a kind of concession to these wider cultural attitudes. Designers will recognise, as Terry Winograd articulates so beautifully below, that the nature of the design process is much subtler and stranger than drawing a straight line between a problem and a solution.

“There is no direct path between the designer’s intention and the outcome. As you work a problem, you are continually in the process of developing a path into it, forming new appreciations and understandings as you make new moves.”

— Terry Winograd

All this is to say that, even as we venerate great design, I believe we tend to undervalue the freewheeling and unpredictable role of imagination in the design process. I believe we don’t assert enough that when we design something it is first and foremost a work of imagination, something we first see in us and then bring into the world. We feed our inner worlds of course with data, insights and experiences. And we use tools to help what we see survive its transit to the real world beyond. But it comes from within us, from the vibrant and occasionally disorientating city of our imaginations.

Perhaps the mystery of this process is unsettling to us, and we prefer to tidy it away behind the more logical and reasonable parts of our mind. But because of this, I think we also tend to undervalue activities like dwelling, pondering and playing. These quiet ways in which we nurture and enrich our interior sight, so that the visions it provides for us might become a little more clear.

When I was a child, the unlikely refuge of my imagination was a set of Jenga blocks. At some point I ceased playing with them as I was supposed to, and instead began to construct elaborate structures on the carpet of the living room. To anyone’s eye but mine I suspect they looked unremarkable. Precariously balanced columns and beams arranged in a loosely geometric pattern on the floor. Painful to step on, but otherwise innocuous enough.

But what I remember is how richly detailed these blocks appeared to me. How I could see the fluting on each column and the flights of steps up to them. The balconies, handrails and double-doors. I could float around these cities in my mind, looking down on the markets, temples and bathhouses that appeared as vividly to me as an illustration. And when the family dog came in wagging destruction, my mind would transform the canine interference into some natural disaster whose terrible wrath I saw played out like a movie on the carpet.

As I grew up, I began to try to bridge the gulf between what I could see in my mind and what was in front of me by drawing elaborate plans and sections on graph paper. There is probably a pile of them going yellow in an attic somewhere. I was always hopelessly ambitious so most of them only have a corner completed before my attention dispersed. But I see in the imagination of my seven or eight year old self, and the sincerity with which he tried to bring what I saw into the world, a quality that I would like to hold on to.

Enjoying Design Lobster? Share it with a friend, colleague or fellow designer 🤲🦞

At this point I want to introduce a wonderfully untranslatable German word: Weltschmerz.

Originating from Welt (“world”) + Schmerz (“pain”), the term describes a feeling of word-weariness or melancholy at the human condition. It was coined by the German novelist Jean Paul in his novel Selina, and the word gives a flavour of the Romantic worldview. Perhaps the most evocative articulation of the feeling comes from the author John D. MacDonald – “homesickness for a place you have never seen.”

I think I probably am a bit of a Romantic—at least in the 18th century German sense—but I include this term in this essay as I believe, for some designers at least, such a feeling can form a shadow behind us that we might be reluctant to acknowledge. Because to be a designer is to live half in this world and half in another, better one which no-one else can see but you. A world which routinely fails, for one reason or another, to materialise. Though I love MacDonald’s turn of phrase, the problem for us is different—that we see the place we have not reached all too well.

And I will confess that this disappointment has occasionally got the better of me. Resentment at the feature cut or mangled, the cheaper or more lucrative option chosen. I know it is not terribly productive to feel these things, that communication matters, that stakeholders can be managed etc etc. But just sometimes, the gulf between the world as it is, and as it could be can feel a little hard to bear. I suppose I am writing this to you because I suspect you too have probably been disappointed at some point. And I propose that just as grief is the price we pay for love, so disappointment might be the price that we pay for imagination.

That is how it is for me at least. And whilst I did not write this essay to provide a remedy, if there is something to take from the occasional bout of Weltschmerz it might be a renewed commitment to the wonders of our mind’s eye. For you alone can see how much poorer the world is without them.

In other words, we designers, to borrow Jeff Bezos’ much-repeated phrase, should also be mindful of the divinity in our discontent. Even if we are propelled by darkness from time to time, we should never stop reaching ahead.

But at this point, a caveat. I have written this essay as support for our neglected inner eye, but it should not be read as endorsement of megalomania. It is not difficult to conjure up all the terrible examples of visions and utopias imposed upon the world against its will, or, to narrow the focus for a second, the terrible products that nobody asked for.

The nourishment we give our inner sight is essential, be that formal research, conversations or simply nice things. And the manner in which we share what we see also matters a great deal, alongside the environments we create for others to share what they can see too. Neither in other words, for this author, the ivory tower or the banged fist.

“The best way to learn is to interact with the world while seeking to understand it, readjusting our mental schemes to what we encounter and find.”

—Carlo Rovelli

In fact I felt this quote from physicist Carlo Rovelli did a better job than I could of getting across the nuance I am trying to convey. We should nurture our interior worlds yes, but not fix them in place, or prevent new information from changing them. Even an inner eye must be kept open.

“Thinking about interfaces is thinking too small. Designing human-computer experience isn't about building a better desktop. It's about creating imaginary worlds that have a special relationship to reality-worlds in which we can extend, amplify, and enrich our own capacities to think, feel, and act.”

—Brenda Laurel

I wanted to finish with this quote from designer Brenda Laurel whose wonderful book Computers as Theater I am reading at the moment. Her quote articulates something that that drew me to software design, namely the possibility to create new imaginary realities for people that empower them in some way.

Software exists at the threshold of imagination and reality, bringing into the world concepts, ideas and relationships that previously existed only in our mind. Just as Hokusai dreamed at age 100 of images indistinguishable from life, I dream of a world when I’m 100 where our imaginations have been unleashed by tools that further narrow the gap between what we imagine and the world beyond.

I think my seven-year-old self would approve.

Hope you imagine something wonderful this week,

Ben 🦞

Enjoyed this essay? Let me know by clicking the heart button below.

👇

I encountered it in Vivasek Veerasamy’s excellent essay on seriousness, which I highly recommend reading.

This is a wonderful phrase: 'And I propose that just as grief is the price we pay for love, so disappointment might be the price that we pay for imagination.'

"we see the place we have not reached all too well"

You've put to words a feeling I've never been able to formulate. Beautifully said.