Unlocking things: an essay

How a 17th century lock might offer a better way to think about our privacy on the internet.

Hello!

This week I’m serving you an additional longer essay that makes connections between a piece of historical design and a contemporary issue. Today’s essay explores what John Wilkes’ 1680 Detector lock can add to the current debate about online privacy.

Has this email been forwarded? Sign up below to get the weekly emails delivered to you. ✏️

Have you ever stared at the ‘lock’ screen on your phone and wondered why it is called that? It’s a mechanical metaphor repurposed for the digital realm with – as we’ll see – mixed success. To understand why it’s there let’s quickly review the history of the lock.

The first lock

The very first locks were simply a hand-sized hole in a door, through which somebody could put in their arm and lift a bar on the other side. Not terribly secure. Over time, this hole became smaller so that only a narrow wooden stick could fit through to lift up the bar. The great innovation came around 4000 years ago in Egypt when a series of wooden pins were added to this bar. These pins could be designed to fit with a set of sliding pegs and lift them out of a bar when the stick was inserted – enabling the bar to be lifted and the door to be opened.

Now, only the owner of this special stick – the key – could get into a particular place. That person could put things in this place that no one else could access. A significant milestone in the history of privacy and security.

Over the Roman period, this technology was perfected, improvements in metallurgy meant that keys began to be made out of more durable metal and locks could be made smaller. This meant smaller things like boxes could be made lockable, as well as homes and rooms. The basic principle remained the same however, a series of sliding pegs (now known as tumblers) that matched the pattern of pins on a key and allowed a bar holding shut a door (or lid) to be shifted.

Even in the centuries that followed, designs did not deviate much from this principle, only embellishing it in certain respects. One notable advance arrived in 1680 in the form of John Wilkes’ Detector Lock which we last discussed in Design Lobster #23. This lock concealed its operations behind a jaunty brass figure – to secure the mechanism you had to press down on his hat and the key could only be entered once you had swung up one of his legs.

Most interestingly, it added a mechanical counter to the mechanism that increased by one every time the lock was opened. In the image above you can see the brass man pointing his staff to the current number. This innovation solved a vulnerability of keys – that if they are taken and used to open a lock there is no way for the key’s owner to know. With the Detector Lock they need only memorise what the number was on the dial the last time they opened it and check this has not changed. Not as good as preventing access at all. But significantly better than nothing.

Despite its benefits, this kind of lock remained mostly a curiosity. The mainstream of locksmithing remained focussed on the security of the lock mechanism itself, rather than detection of potential misuse of the key.

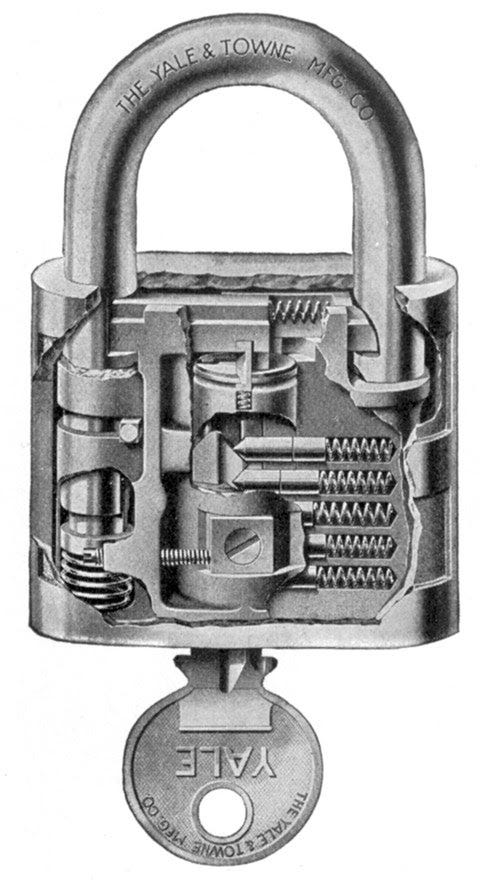

So it was that in 1861, one Linus Yale Jr became a household name by adapting the pin tumbler design invented by his father so that it would accept a smaller key with a serrated edge. The eponymous Yale lock offered no detection features but offered a high level of security even when embedded within the body of a door or in small padlocks like the one shown above. Mass-produced, the design became hugely popular in the US and Britain and will be familiar to many readers. Though technically impressive, the principles of the lock are hardly different from our original Egyptian example.

Locks: a mental model

Because of our familiarity with the technology, the mental model of a lock is easy to understand. We know that the lock creates a ‘locked place’ which can only be accessed by somebody possessing the key. By extension we intuit that things inside that place cannot be accessed, and things outside it can be. I’ve tried to summarise this mental model in the diagram above. I think this mental model is how we approach keeping things on the internet too – and I think that’s a problem

Mechanical metaphors, digital privacy

Every day the average person produces an astonishing 144Gb of data as they move around the internet. I think it’s helpful to think of this huge cloud of data points as possessions of a sort. Of course unlike the things we keep locked up at home, these possessions are essentially invisible and can move around the world without us being aware. And there are literally quintillions of them. More than we could ever possibly know.

Now, Yale lock and key icons are everywhere in modern software. When we ‘unlock’ our phones, when we log into a website with a password and when we pay for things, a digital version of that icon is never hard to find. The implied mental model is exactly that of house or car keys. The phone or the website is the locked place, your face, fingerprint or your password is the key. By extension, though our rational brains might tell us otherwise, it feels like once we turn that digital key that everything past that point is accessible only to us, is private and safe.

Apple even played on this feeling with an advert last year on a billboard in Las Vegas. Using the tag line “What happens on your iPhone, stays on your iPhone.” Literally untrue, it plays on an implied mental model of the phone as a ‘locked place’ whose contents are sealed within so that only we can access them.

Your stuff, in someone else’s safe

Of course on the internet, and especially in particular parts of it, that’s not at all how things work. Despite the reassuring icons, the fact remains that online we are nearly always entrusting our possessions to third parties. It might feel like you’ve got your stuff locked up behind a password on your phone but those photos, emails or text messages are being kept in another company’s servers in (most likely) a completely different part of the world.

The business model of some of those their parties might give us further pause. When Facebook (for example) puts a lock icon on their log in screen they want their users to feel they are turning a key to their own safe. But this safe – if we can call it that – is owned by a company that keeps a track of your possessions and indeed auctions what it knows about them to third-parties to make money.

The involvement of third parties makes online privacy and security an entirely different ball game. Below I’ve tried to update my mental model diagram to reflect the way our digital possessions are actually kept.

An alternative paradigm for online privacy

To communicate how to use new technology, designers often have to use mental models from previous technological eras to give users a helping hand, even if these metaphors don’t map perfectly onto the new situation. I think we are reaching the limit of what the lock and key model can communicate in our digital world. What does it mean to use a lock icon with possessions so scattered, numerous and invisible? What use is a secure key when the safe belongs to a third party that has its own agenda for the stuff it keeps on our behalf?

It’s in this context that I think John Wilkes Detector Lock presents an interesting alternative paradigm. The innovation of this lock was to detect when it had been used, giving you some visibility of when that use might not have been authorised. I would argue that online, where our possessions are in third party hands by default, a similar approach is needed. What if the activity of these third parties could be visible to us? What if we could see when our digital possessions were being moved about – and indeed used for commercial reasons?

I see some of the changes that Apple has made in iOS 14 as forerunners of what this paradigm might look like. Over the summer, as beta-testers began to try out the new software they noticed a new type of alert in some apps indicating that the contents of their clipboard were being pasted. Big companies including TikTok and Linkedin were shown to be indiscriminately hoovering up this data with no clear reason. The alerts made a hitherto invisible action of these third parties visible to the user and in the outcry forced companies to be more responsible and transparent about collecting this kind of data.

Apple’s other changes include warning lights when an app is accessing the microphone or camera and a new (highly controversial) permission request when apps want to track you across the internet. Effectively, these are detector mechanisms pointed towards the many third parties that are the custodians of our digital possessions. We could imagine even more sophisticated ones. What if we had tools for understanding the data collected about us on social media that were as extensive as those offered to advertisers to track campaigns?

I see the Detector Lock of 2020 – let’s call it detector.io – as a digital update to the John Wilke’s locksmithing of three and a half centuries ago. Instead of a simple rotating dial, imagine a dashboard with a glanceable summary of both what data was being kept about you and the circumstances in which it was being used by companies to make money. It might alert you when significant changes occurred, perhaps you would even be able to ask a jaunty chatbot in a Tudor hat your questions or concerns.

Now, some of you reading this might point out that it is already possible to download a full copy of your data from Facebook and other social media sites. But anyone who has done so will also be aware how immensely difficult it to glean anything useful from this exercise. What if your data wasn’t presented as just a dump of confusing text logs but instead as a tool that was as delightful to use as a hand-crafted lock?

Now, it’s not my argument in this essay for us to do away with passwords or two-factor authentication. Making our digital locks hard to pick is still an important consideration. But I think the emphasis of the debate needs to shift from the security of our locks to the ability of those locks to detect activity in and out of the places they protect.

I’d like to see a future where detection mechanisms shine a light on the ocean of invisible activity occurring in our implied ‘private’ spaces. And I believe users would have more trust in the third party storage of their data if those same third parties committed to high standards of detection as well as conventional security.

I leave you with the words carved on the original 1680 Detector Lock. When I read them now, I hear John Wilkes’ speaking across time to Mark Zuckerberg.

If I had ye gift of tongue

I would declare and do no wrong

Who ye are ye come by stealth

To impare my Master's wealth.

Enjoyed this essay? Let me know by clicking the heart button.

👇

Benjamin, great read! I loved the history and mental model. Thanks for writing about the security space! We desperately need more and better design perspective.

It occurs to me that a version of detector.io for consumers exists but it resides in the hands of the third parties that we entrust our data and storage hardware to. Google or Apple, for example, will inform me if they have detected "unusual" sign-on activity in my account or device. I find this to be a nice utility but again, the paradigm remains that the right to view access is maintained by third parties.

Great post to stimulate thinking around privacy choices.