Design Lobster #89 is small but perfectly formed. This week, we’re visiting an Irish summer house that uses some clever illusions to diminish its true size and admiring some extraordinarily detailed model insects. A petite start to the week. ⚛️

✨Enjoying Design Lobster? Please share it with a friend, colleague or fellow designer.

Question: How can you make a large building appear small?

The Casino at Marino near Dublin in Ireland was designed in the 1770s by architect William Chambers for his friend the Earl of Charlemont. The Earl had become fascinated with all things Italian after his Grand Tour, even going to the lengths of naming his estate after the town of Marino in Lazio. Inspired by his journey, he asked Chambers to design him a summerhouse in the Classical style, which would sit in the grounds of a hunting lodge called Marino House. It was to be called the Casino after the Italian for ‘little house’.

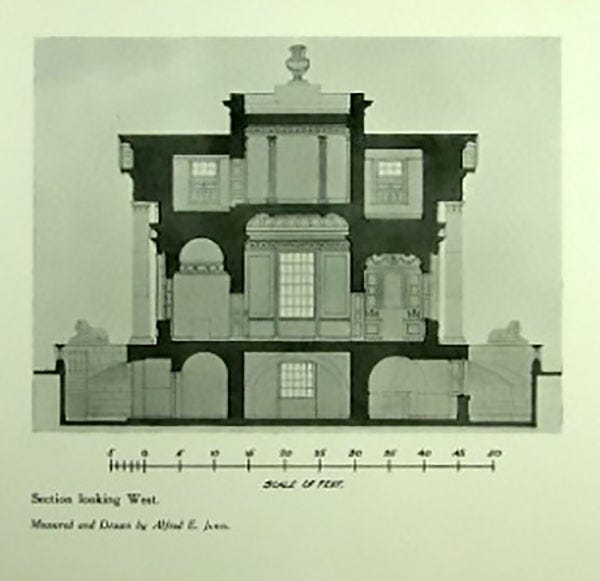

Chamber’s design ingeniously concealed sixteen rooms and three stories within an apparently single-story Greek temple. The single windows light multiple rooms behind them and make use of concave panes to disguise this fact from the outside. The over-scaled urn on the roof contributes to the illusion of petiteness and also doubles as a chimney. In a similar manner, each column is hollow and operates as a concealed drainpipe. Some of this trickery can be seen in the section below.

Chambers skill at hiding the buildings true organisation behind an elegant facade feels somehow very contemporary. I can’t help but feel that Steve Jobs might have made good use of his skills at Apple had he been born two centuries later. But more than anything I love this building’s ability to surprise. In the best design there is always more than meets the eye.

Design takeaway: How could you change the apparent scale of your design?

🏡 Watch a short video about the Casino

Object: Papier-mâché insect models

As a medical student in 18th century France, Dr. Louis Jerome Auzoux was inspired by a visit to a papier-mâché workshop to change the way biological specimens were modelled. His own studies were being hindered by the difficulty in obtaining and working with real cadavers or highly fragile wax models, which were then the norm. Developing an approach he went on to call Anatomie Clastique, Auzoux began making models from hardened paper paste that were durable enough to be disassembled and reassembled, making the study of both human and zoological anatomy far easier.

Auxoux’s creations became very popular and he opened a factory in 1825 to meet the demand. Over the course of it’s production over six hundred different types of models were created, ranging from those showing the human foetus to these delightful (and rather frightening) enlarged insects. I’ve always admired model-making as a way of advancing our understanding and I think these papier-mâché creatures are a terrific example.

Design takeaway: Could a beautiful model help improve your design?

👁A short video showing a model of the human eye by Auzoux

Quote: “We only know what we make.”

– Giambattista Vico

Vico was a Counter-Enlightenment scholar who lived between 1668 and 1744. This, his most famous quote, encapsulates his highly pragmatic worldview. I think designers know better than anyone the importance of making things – models, prototypes and more – to truly understand a situation or idea.

Whatever you do, keep making.

Ben 🦞

Enjoyed this week’s Design Lobster? Let me know by clicking the heart button.

👇